First, let’s back up. Tissue is sent by your primary or dermatologist for pathology to answer one of two questions: “what is it?” or “did I get it all?”

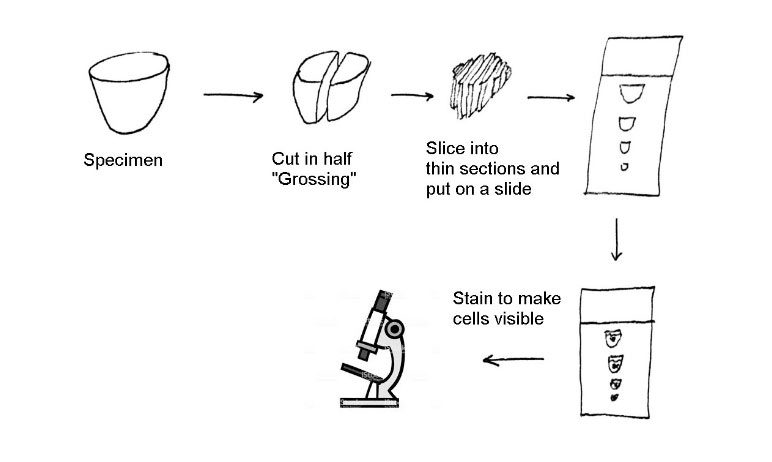

The question of “what is it?” is answered with the initial sampling, or biopsy. A piece of skin (or other tissue) is removed from a patient, preserved (or “fixed”) in formalin, sliced into thin pieces, stained so that cellular detail can be seen and then examined under the microscope. In dermatology, biopsies are performed to diagnose rashes as well as to evaluate for skin cancer.

Outline of steps to process a piece of tissue so that it can be examined under the microscope

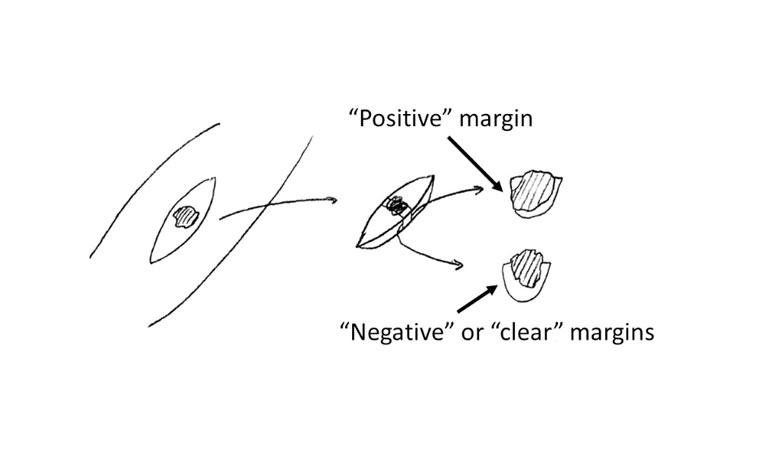

Outline of steps to process a piece of tissue so that it can be examined under the microscopeThe second question of pathology is “did I get it all”. This is also called margin assessment. When a cancer is removed, the surgeon (and patient) want to make sure it’s all gone. The standard way of doing that check is to make sure that there is normal tissue around the cancer and that no cancer is touching the outer portion of the removed tissue. The idea is that if tumor is on the outside of the specimen, then there may still be some left in the patient. Having normal tissue all around the specimen is called “clear margins”.

Assessing margins of tissue

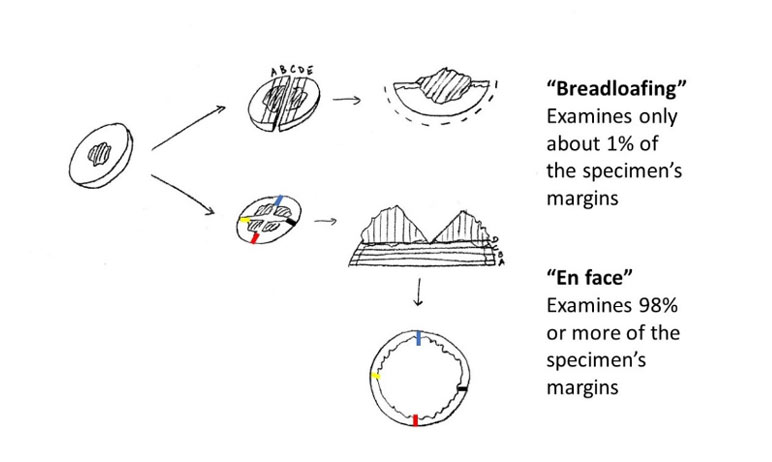

Assessing margins of tissueThe methods shown above to process tissue and assess margins is known as “breadloafing”, in that it is similar to slicing bread. The problem with this “breadloafing” method for margin assessment is that only a small portion (less than 1%) of the margins get examined, so even if all examined bread-loafed margins (less than 1%) are clear, there is still a potential for tumor to present in an unexamined area (the remaining 99%).

“Breadloafing” versus en face tissue processing

“Breadloafing” versus en face tissue processingMohs surgery relies on processing tissue en face (as above). The tumor is removed, but then grossed so that the peripheral rim of tissue can be laid down in the same plane (such as on a microscope slide). Then, colored inks are placed so that a map of the tissue can be made. This enables latter orientation of the tissue under the microscope. This tissue is then frozen and thin sections are made in a machine (called a cryostat) and stained so that cellular details can be seen. The processing of this tissue takes about 30 to 60 minutes. For some wounds, the surgeon may decide to use that time period to stress-relax the wound to make it easier to close once the margins have been cleared. The SUTUREGARD ISR device can be very helpful in that regard.

The Mohs surgeon will examine the slides under the microscope. If there is a complete outer rim of epidermis, then the surgeon is confident that she is visualizing the entire peripheral and deep margin of the specimen. If there is no tumor seen, then the deep and peripheral margins are “clear’ and the wound can be reconstructed. If a margin is “positive” for tumor, then the surgeon can note where there was tumor relative to the colors in the map and take more tissue. This process is repeated until the margins are clear.

The Mohs procedure has a very high (97% or more) cure rate and is considered the “gold standard” treatment modality for many skin cancers such as basal cell carcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma.

Why the name “Mohs surgery”? It was developed by Frederic Mohs in the 1930s. He developed a paste to “fix” the tissue on the patient’s body, instead of freezing the tissue and using a cryostat. Most use the frozen section method or “fresh tissue technique” as described here, but the name continues to honor Dr. Mohs.

You can learn more about Mohs Surgery and find fellowship-trained Mohs surgeons at mohscollege.org